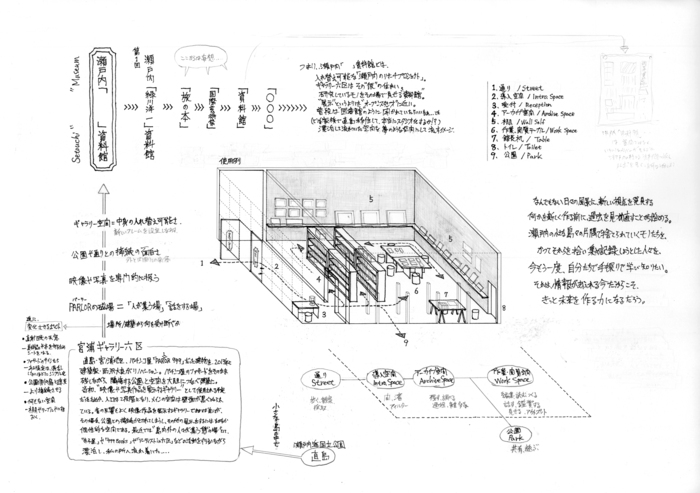

[ 瀬戸内「 」資料館 /Setouchi " " Archive ]

Project

2019−

瀬戸内「 」資料館

なんでもない日々の風景に、新しい眼差しを発見する。

何かを新しく作る前に、過去を見つめ直すことから始める。

瀬戸内の小さな島々の片隅で捨てられていくモノたちを、

かつてそれらを拾い集め記録しようとした人々を、

今もう一度、自分たちで手探りで知り学びたい。

それは、情報が溢れる今だからこそ、

きっと未来を作る力になるだろう。

瀬戸内「 」資料館は、

瀬戸内の風景の中から毎回「何かしら」のテーマを決めて、

メンバーと共に調査し発表しアーカイブするプロジェクト。

いつもは観光客がふと足を止める小さな「図書館」や「博物館」のような場所として、

時には様々な人が集まる「研究所」や「塾」のようなささやかな学びの場として、

島民の元娯楽の場「パチンコ999」を改装した「宮浦ギャラリー六区」をさらに改装して、

アートを目的に多くの人が訪れるこの島に生まれた。

下道基行 (資料館館長)

Setouchi " " Archive

Discover a new way of looking at the scenery on an average day.

Before you create something new, it all begins by taking another look at the past.

Goods that get thrown away in the corners of the small islands of Setouchi,

and the people who once sought to collect and record them,

we want to know and learn about these things once again with our own hands.

In an age such as today which has an abundance of information,

it will surely be a key in helping to create the future.

In the Setouchi " " Archive project,

with "a certain" theme taken from the scenery of Setouchi every time,

we will survey, present, and archive together with our members.

It can be a place, generally like a small library or museum for the tourists to visit on a whim,

and sometimes a laboratory or academy for various people to visit for a modest learning experience.

Refurbishing Miyanoura Gallery 6, which itself is a refurbishment of the island residents' former place of amusement, Pachinko 999,

the museum is born, in the island where many people visit for art.

Motoyuki Shitamichi (Chief Director of the Archive)

:::::::::::::::::

なんでもない日々の風景に、新しい眼差しを発見する。

何かを新しく作る前に、過去を見つめ直すことから始める。瀬戸内の小さな島々の片隅で捨てられていくモノたちを、かつてそれらを拾い集め記録しようとした人々を、今もう一度、手探りで知り学びたい。

それは、情報が溢れる今だからこそ、きっと未来を作る力になるだろう。

(『瀬戸内「 」資料館』パンフレットより)

「瀬戸内「 」資料館」というプロジェクト/スペースを生まれ育った地域の小さな島で始めた。これまでのシリーズ作品のように、自ら風景を撮影しながら作品を作ることはしない。瀬戸内の島々のフィールドワークを行い、既にこの地域を記録してきた写真家やその他の人々に新しい光を当てる。そして、残された写真や記録物などを収集し、展覧会を開き、ゼロから“ 見える収蔵庫 ”を作っていく。時間が経つにつれ、この収蔵庫は、地元民や旅人が立ち寄れる瀬戸内の島々に関する図書館/ 郷土資料館になるだろう。この資料館を通して、過去と未来という時間をつなぎ、さらに別の国や地域と空間をつないでいきたいと考えている。

Discover a new look in the everyday scenery. Start by looking back at the past before making something new.

I would like to find out and learn about the things that are being thrown away in the corners of the small islands of Setouchi, and the people who once tried to collect and record them.

It will surely be a force to create the future because it is full of information now.

(From the Setouchi “ ” Archive pamphlet)

I started a project/space called the Setouchi “ ” Archive on a small island in the region where I was born and raised. Unlike my previous works, I am not shooting landscapes to make my art. Instead, I am conducting fieldwork on the islands in the Seto Inland Sea to shed new light on photographers and other individuals who have spent years recording the region. I collect the photos and records that have been left behind and curate exhibitions, creating what I call a “visible storage archive” from the ground up. Over time, the collection can become a local library/ museum where locals and travelers alike can stop by to learn about the islands of Setouchi. I hope that this museum can link the past with the future and connect this space with others in different regions and countries around the world.

:::::::::::::::::

第3回 瀬戸内「 」資料館

[ 03 瀬戸内「鍰造景」資料館 /03 Setouchi " Slag Landscape " Archive ]

宮浦ギャラリー六区(直島)

2021年8月14日(土) -9/12

毎週土曜日/無料

宮浦ギャラリー六区

瀬戸内「百年観光」資料館

プロジェクト名:瀬戸内「 」資料館(下道基行)

写真:宮脇慎太郎

協力:公益財団法人 福武財団

03 瀬戸内「鍰造景」資料館

《瀬戸内「 」資料館》の第三弾のテーマは、銅を製錬する際に排出される不純物/廃棄物である鍰がつくる風景を、『鍰造景』と題して調査発表する。※1

直島の朝と夕方、多くの人が集落や港から島北部の工場へと往来する。島に移住して気がついたこの光景は、直島の素顔の一つかもしれない。人々が通勤するのは銅の製錬所。直島が“アートの島”になるずっと昔から島を支えてきた巨大産業である。1917年に創業し、今でも島民の多くがこの「三菱マテリアル」に従事し、島はこの産業によって潤ってきた。ただ、観光客の多くは、山の向こう側に100年以上も続く、工場地帯が隠れていることに気がついていないのではないか。

「昔、製錬所で出た鍰は、熱いままドロドロの状態で小さな電車に引かせて、敷地のなかに捨てていたんです。鍰捨電車って呼んでいたかなあ…。1950年頃から10年間くらい、鍰を鋳型に鋳込んで煉瓦や瓦などを製造していました。煉瓦は三菱の社宅の外壁だけではなくて階段や台所とか様々なところに使われて、「才ノ神」集落に並ぶ社宅の屋根は鍰でできた瓦屋根が多かった。もう社宅は壊されたけど、あの瓦はどこに行ったのだろうねえ…。」(島民の話)

島で銅製錬がつくり出す風景は、日々の通勤風景だけではなく、目を凝らすと、実は島の風景のあちこちに深く刻まれているのに気がつく。それが今回の展示テーマである「鍰」だ。銅の製錬時に大量に排出され“厄介者”である「鍰」。それを鋳型に流し込んで成型した鍰煉瓦は、住宅の基礎や壁などに建材として利用され島の風景の一部となっている。本展示では、銅製錬の産業自体ではなく、それによって排出された「鍰」がどのように形を変えて風景の中に残されているのかに着目する。

2020年4月、直島の風景や歴史に興味を持つ島民2人(岡本雄大、アンドリュー・マコーミックと共にプロジェクト「直島鍰風景研究室」を立ち上げた。※2 3人はそれぞれの日常生活のなかで見つけた鍰を撮影しマッピングを続けた。その調査のなかで、鍰の再利用は、煉瓦だけではなくタイルや瓦といった様々な形で島内に残されていることや、さらに三菱の社宅が立ち並ぶ集落に特に多く残されていることなどが、徐々にわかっていった。鍰煉瓦は「新宮浦」と呼ばれる一帯では社宅は取り壊されていたものの、住宅の土台や外壁に多く残されている。反面、20年以上前に取り壊された「ヘキ」「才ノ神」「鷲ノ松」集落では微かに現存するのみ。ただ、取り壊された社宅の「鍰」煉瓦や瓦は近年、別の場所に運ばれ新しい住宅やお店などに“おしゃれなワンポイント”としてさらに再利用され始めていた。60年以上前に生産を終えた鍰の建材は、その存在価値を時代によって変化させてきている。(現在、製錬所で出る鍰は水で急冷し、砂状の水砕鍰にして、セメントの鉄原料などとして利用されているそうだ。)今回、「直島鍰風景研究室」の1年以上に及ぶ調査の成果は、この展示《瀬戸内「鍰造景」資料館》と『直島鍰風景地図』の出版という形にした。この地図が島を訪れる人々にとって島の近代産業と島民の生活風景の結びつきを感じる新しい直島ガイドブックの一つになることを願う。

さらに、私自身は、直島だけではなく、日本全国の『鍰造景』を巡るようになる。※3 それはこの直島での調査を進めるなかで、実際に銅の採掘や銅製錬の歴史を持つ他の地域を見てみたいと思うようになったからだ。その取材のなかで目の当たりにしたのは、どこの地域も銅製錬の輝かしい時代が語られると同時に、公害の問題と向き合わざるを得なかった過去。茨城県の日立鉱山が描かれる小説「ある町の高い煙突」(新田次郎著、文藝春秋者、1969年)は、1920年代に製錬所から排出される「煙」害と向き合う人々と企業との前向きな物語であるが、その一方で様々な地域に暗い影を落とす場面にも多く遭遇した。

「鍰」は“金屎(かなくそ)”とも呼ばれる。人も何かを食べればクソが出るように、巨大産業も生産すれば廃棄物が出てしまう。人のそれは川に垂れ流すと川が汚れるので昔はよく畑に撒いて肥料にしていたが、巨大産業の廃棄物も自然環境に垂れ流せば公害になり、『鍰造景』は近代産業の廃棄物を生活の中にリサイクルする試行錯誤の痕跡とも言える。日本より早く近代化を進めたヨーロッパでは20年以上前から『鍰造景』は近代化遺産として史跡化が始まっている。日本における明治以降の急激な近代化の中で、戦争とも結びつきながら生産を激増させた過去は、公害や労働者の問題と結びつきアンタッチャブルな問題になっている。ただ、近代の歪みが生み出した『鍰造景』は今の私たちに語りかける。その声に耳を澄ましてみてはどうだろう。

※1 三菱マテリアルは鍰を廃棄せず、銅スラグとして販売しているため、廃棄物ではなく不純物と表記する。

※2 「直島鍰風景研究室」 https://www.instagram.com/naoshimakarami/

※3 「日本鍰造景資料館」 https://www.instagram.com/japanslagscapearchive/

下道基行(瀬戸内「 」資料館 館長)

03 Setouchi " Slag Landscape " Archive

The third theme of the Setouchi “ ” Archive, entitled “Slagscapes,” involves the surveying and showcasing of landscapes created by slag (karami), an impurity or waste product released during the smelting of copper ore.1

On Naoshima, every morning and evening, many people travel back and forth from the villages and ports to the factories on the northern part of the island. This scene, which I became aware of only after moving to the island, may be one of the true faces of Naoshima. These people are commuting to the copper smelter, part of a heavy industry that has supported the island long before Naoshima became the “Island of Art.” Founded in 1917, Mitsubishi Materials still employs many islanders even today in an industry that has brought prosperity to the island. However, many tourists may not be aware that beyond the mountain lies a hidden factory complex that has been in operation for over a century.

In the old days, they used a small train to haul the slag produced by the smelter as a kind of hot slurry and then disposed of on site. I seem to remember they called it the karamisute densha (“slag disposal train”)… For about ten years from around 1950, the slag was cast into molds to manufacture things like bricks and roof tiles. The bricks were used for the Mitsubishi company housing – not only for the building facades, but for the stairs, kitchens, and various other places, as well – and many of the roofs of the company houses that lined the streets of the Sai-no-kami settlement were tiled with tiles made from slag. Those company houses have all been torn down now, but I wonder what happened to those tiles…. (Islander’s story)

The island landscapes created by the smelter are not limited to the scenes of the daily commute; pay close attention and you will see that they are actually deeply engraved here and there in the island scenery. This is the slag that represents the theme of our exhibition. Slag – a “nuisance material” that is released in large quantities when smelting copper. Slag bricks, which are shaped by pouring slag into a mold, have been used as a building material for the foundations and walls of houses, becoming a part of the island landscape. In this exhibition, rather than the copper smelting industry itself, we focus on how the slag it produces has been transformed and preserved in the landscape.

In April 2020, together with Yudai Okamoto and Andrew D. McCormick, two island residents interested in Naoshima’s landscape and history, I launched the Naoshima Karami Landscape Laboratory.2 The three of us continued photographing and mapping the slag we each came across in the course of our daily lives. In conducting this survey, it gradually dawned on us that the reuse of slag had led to its being retained on the island in the form of not only bricks, but also of tiles and roofing tiles, and that these were particularly significantly preserved in the settlements that were the sites of Mitsubishi’s company housing. Despite the fact that the company housing had been torn down in the area known as Shin Miyanoura, many slag bricks remain on the foundations and facades of private residences. On the other hand, in the Heki, Sai-no-kami, and Washi-no-matsu settlements, which were demolished over twenty years ago, only a scant few examples remain. Nevertheless, in recent years, the slag bricks and roofing tiles from the company housing have been relocated to other sites around the island and have moreover begun being reused as stylish architectural accents in new homes and shops. More than sixty years after their production was discontinued, slag building materials are taking on a new value in the contemporary age. (Currently, the slag produced at the smelter is rapidly cooled with water to become a sandy, granular substance that is apparently used as a ferrous raw material in the production of cement.) Now, the results of more than a year of survey work by the Naoshima Karami Landscape Laboratory have given shape to this exhibition, the Setouchi Slagscape Archive, and the publication of the Naoshima Karami Landscape Map. It is our hope that, for visitors to the island, this map will serve as a new Naoshima Guidebook that will give a sense of the links between island’s modern industry and the islanders’ lived landscapes.

Furthermore, I myself am now touring “slagscapes” not only on Naoshima, but across Japan.3 This is because in proceeding with our survey on Naoshima, I developed a desire to actually see other areas that have a history of copper mining and smelting. What I witnessed in this fact-finding process, at the same time as the illustrious age of copper smelting, was a past that had been forced to confront the problem of pollution. In Jirō Nitta’s 1969 novel Aru machi no takai entotsu (The Tall Smokestack of a Certain Town) published by Bungeishunju Ltd., despite its being a positive story of the people and businesses confronting the smoke pollution being emitted by a smelter at the Hitachi Mine in Ibaraki Prefecture in the 1910s, the reader nevertheless also encounters many scenes that cast dark shadows on various areas.

Slag is also referred to with the Japanese word kanakuso (“metallic excrement”). Just as human beings must defecate after eating, so does production by heavy industry entail the discharge of waste. In the past, people used to sprinkle excrement (called “night soil”) on their fields as fertilizer, since discharging into the river would sully the waters. But if waste products from heavy industry are leaked into the natural environment, they become pollution. “Slagscapes” could be characterized as the traces of a process of trial and error in the attempt to recycle modern industrial waste products within the sphere of daily life. In Europe, which modernized earlier than Japan, “slagscapes” have been starting to be recognized as historical sites evoking the heritage of modernization for over twenty years. During the period of rapid modernization that began in Japan with the Meiji era, the past – in which production increased sharply in connection with wars – has become an untouchable problem linked with pollution and labor troubles. And yet the “slagscapes” created by these distortions of modernity still speak to us today. Why not try to listen to that voice?

*1 Since Mitsubishi Materials does not dispose of karami but rather sells it as copper slag, it is described in terms of an “impurity” instead of a waste product.

*2 Naoshima Karami Landscape Laboratory (https://www.instagram.com/naoshimakarami/)

*3 Japan Slagscape Archive (https://www.instagram.com/japanslagscapearchive/)

Motoyuki Shitamichi (Director, Setouchi “ ” Archive)

:::::::::::::::::

第2回 瀬戸内「 」資料館

[ 02 瀬戸内「百年観光」資料館 /02 Setouchi " Hundred Years' Tourism " Museum ]

宮浦ギャラリー六区(直島)

2020年7月4日(土) オープン!

毎週土曜日/無料

戦前から現在までの瀬戸内の旅行ガイドブックを収集し、瀬戸内の観光について知り考える場を作ります。

宮浦ギャラリー六区

瀬戸内「百年観光」資料館

プロジェクト名:瀬戸内「 」資料館(監修:下道基行)

写真:下道基行

協力:公益財団法人 福武財団

02. 瀬戸内「百年観光」資料館

《瀬戸内「 」資料館》の第2回のテーマは、『百年観光』と題して、瀬戸内と直島の観光の歴史を調査発表する。

展示は、瀬戸内の観光や交通の歴史を調査し自作した「瀬戸内観光年表」と「直島観光年表」を、今回収集した既刊の「旅行書」とリンクさせつつ、時系列に並べて構成している(観光という言葉自体が作られ普及したのが近代以降で、実質的に『百年』程度と歴史は浅い。よって、観光年表は近代以降より制作した※1 )。

現在「アートの島」として特集が組まれるほどの直島は、数十年前にはどのように扱われていたのか。調査はそんな素朴な疑問から始まった。そこで、瀬戸内や直島を扱った旅行書(ガイドブック)を、現在から過去へと徐々に遡りながら収集した。例えば『るるぶ』(JTBパブリッシング発行)の場合、瀬戸大橋開通の1988年に『るるぶ香川』『るるぶ山陽瀬戸内海』が発刊され、以降その両方に直島は掲載されてきた。頻繁に更新されていく多くの旅行書は、過去の物が非常に入手困難ではある反面、発見した場合は安価で簡単に入手できた。過去へ遡って旅行書を読み進める作業は、時間旅行のようだ。

瀬戸内の旅行書で面白いのは「観光コース/ルート」ではないだろうか。それは点と点を線で結び面にしたものだ。瀬戸内の観光は、一つ一つの点(目的地)は広大な地域に散らばっており、それらの点を多彩な線(船や鉄道や車や飛行機)の組み合わせでつなげていく。京都や東京などと比べると、アイコニックな目的地は多くないが、その分、広域に多様なバリエーションがあると言える。

開国以降から明治にかけて、欧米の旅行者によって絶賛された瀬戸内の観光は、船で通過しながら眺めるものだったようだ。さながら動画のような風景を楽しむことがメインの、広く面で捉える観光スタイルだと言える。さらに、『百年』前から日本人の間でも人気のあった瀬戸内の船旅も、大阪と別府温泉をつなぐ線(航路)上にあり、小豆島、高松、松山などの鉄道では行きづらい観光地が点となっていた※2。ただ、近年、観光の移動手段が変化していく中で船旅は廃れ、船から見る瀬戸内の素晴らしさは忘れられていった。

その中で、2010年に突如現れた“新しい観光コース”である瀬戸内国際芸術祭(以下、瀬戸芸)は、船での旅を全面に押し出し、多くの観光客を集めている。現代美術作品を小さな点として島々に配置し、そこを目的地として“巡礼”する楽しさに惹かれた人々は、道中で船に乗り瀬戸内の風景や人々と出会っていく。

一体この“現代アート”の巡礼は人々に何を与えるのだろうか。旅や観光は古くから宗教と結びつき、人々はそのご利益を期待し巡礼してきた。だが、もしかすると、宗教であれ美術であれ、目的地(置かれた点)はある意味で「フィクション/虚構」であり、実はそのプロセス自体(引かれる線)の方に意味があるのかもしれない。

今年3月、私は妻と娘とともにこの直島へ移住してきた。諸々の理由はあるが、私自身の生まれ故郷である瀬戸内の今をより深く知るために、ここに“住む”ことを選んだのだった。ただ、その直後に新型コロナウイルスが流行。4月16日には感染拡大防止のため、全国的に移動や外出が規制された。直島でも観光客は徐々に減っていき、ついに集落は静まり返った。島民たちは「アートがくる以前の30年前に戻ったみたいだなぁ」とささやき合った。観光客が絶えることのない直島が、島ごと数十年前にタイムスリップしたようだった。

直島という小さな島は約『百年』前より三菱の銅の精錬という巨大な産業によって潤ってきた。今でも人口の7割程度が三菱関連の仕事に就く。その直島が観光業に乗り出すのは1960年代から、三菱の機械化・合理化により人口が激減する中、三宅親連町長によって観光への大胆な舵きりがなされていくのがきっかけだ。ピーク時の7725人(1959年)から人口は減り続け、現在3000人程度。逆に、直島へやってくる年間の観光客数は、1990年に1.1万人だったのが2019年には73万人に膨れ上がっている。ただ、この10年で観光客が驚くほど急増している瀬戸内の”小さな島々”は、一方で人口減少に頭を悩ませている。

自然環境とそこに暮らす人々によって長い時間をかけて作られた「風景」は、外の目によって発見され美しい観光財産となる。風景は、さらにコンテンツ/イメージと結びつき、人々を魅了してきた。万葉集の枕詞や歴史絵巻の舞台、映画やゲームの中の世界、現代アートもそうだ。ただ、それらの外の目が作り出したイメージは、時間の経過と共に消費され忘れ去られる。時として、観光は長い時間で作られた風景の形を急激に変えたり、逆に見た目はそのままで中身はなくなり、形骸化させてしまうことがある。(例えば、古い街並みが有名になり保存されるが、観光以外の人々の生活がそこから消えていくケースなど。)長い時間感覚を持った眼差しで、風景と向き合い続ける必要があるのではないか。

私は観光学などの専門家でもなく、直島についてもまだ詳しくない。だから、本展示は私が瀬戸内や直島を調べて知っていく過程にあり、未完成である。この展示は歴史的事実を発見し発表したいのでもないし、自ら芸術品を創作して置きたいのでもない。私はこの展示(資料館というフィクション)を作りながら、『百年』の観光が累積したこの土地の地面を掘り進めるプロセス(線)自体を、展示を体験する島民や観光客と共有することで、瀬戸内や直島の未来を少し想像する場所にしたいと考えている。

最後に、今回、八十年代より新聞の直島の記事を切り抜き貼り付けた貴重なスクラップブックをご提供いただいた田中春樹氏、古い資料やポスターなどを提供いただいた直島町観光協会と直島町役場まちづくり観光課、そしてインタビューにお答えいただいた島民の方々に、この場を借りて御礼申し上げたい。

下道基行(資料館館長)

02 Setouchi “100 Years Tourism” Museum

The second theme of the Setouchi “ ” Museum project is “100 Years Tourism”: a presentation of research into the history of tourism in Setouchi and Naoshima.

The exhibition comprises a Setouchi Chronology of Tourism and a Naoshima Chronology of Tourism, which I created based on research into the history of tourism and transportation in Setouchi and linked to previously-published guidebooks collected especially for this project. (The term “tourism” itself did not come into general use until modern times, and it has a substantive history of just 100 years. This project’s Chronologies of Tourism thus begin in the modern era*1.)

Today Naoshima features regularly in the media as an “art island,” but how was it viewed a few decades ago? This simple interest was the starting point for my research. I began collecting travel guidebooks that dealt with Setouchi and Naoshima, working gradually backwards from the present day into the past. In the Rurubu series (JTB Publishing), for example, the first edition of Rurubu Sanyo Setonaikai was published in 1988, the year that the Seto Ohashi Bridge opened, and Rurubu Kagawa was first published in 1990. Naoshima was included in both these publications thereafter. Many guidebooks are frequently updated and past editions are difficult to obtain, but wherever I could find them I was able to acquire them cheaply and easily. Reading through these guidebooks further and further into the past was something akin to travelling through time.

One of the intriguing features of guidebooks to Setouchi is their tourist courses and routes, which use lines to connect different points. In Setouchi tourism, the points (destinations) are scattered across a vast area, and connected with one another by a diverse combination of lines representing transportation by sea, rail, road, and air. There may be few iconic destinations compared to places like Kyoto and Tokyo, but instead there is great variety across a large expanse of territory.

From Japan’s opening to the outside world through the Meiji period of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Setouchi tourism earned high acclaim among travelers from Europe and North America, who would take in the scenic views as they passed through the region by boat. This style of tourism mainly involved enjoying the scenery as a kind of moving image with a broad, superficial outlook. Trips through Setouchi by sea were also popular among Japanese people from 100 years ago, with Shodoshima, Takamatsu, Matsuyama, and other tourist destinations difficult to reach by rail featuring as points along the sea route that connected Osaka and the hot springs town of Beppu.*2 In more recent times, however, the means of tourist transport have changed: sea journeys have fallen out of vogue and the attractions of Setouchi as seen from the water have gradually been forgotten.

It is in this context that the Setouchi Triennale burst on to the scene in 2010 as a “new tourist route” that attracts many tourists to the region by placing sea travel front and center. Works of contemporary art installed on many different islands serve as points in the tourist route, with visitors fascinated by the idea of making a “pilgrimage” around these destinations and encountering the views and people of Setouchi as they make their way from point to point by ferry.

What exactly is it that people get out of this pilgrimage of contemporary art? Travel and tourism have long been intertwined with religion, as people journeyed from one sacred site to the next in anticipation of the benefits they may gain. However, regardless of whether the pilgrimage is for religion or for art, the destinations (points) between which travelers move could be seen in a sense as “fictions”: perhaps the real meaning lies in the process of movement itself (the lines drawn between the points).

In March this year, I moved to live in Naoshima with my wife and daughter. There were many reasons for this move, but I chose to take up residence here in order to gain deeper knowledge of Setouchi, the place I was born, as it is today. Just after we moved in, however, the novel coronavirus began to spread in Japan. On April 16, restrictions were placed on travel and movement outside the home across the whole of Japan to prevent the spread of the infection. The number of tourists in Naoshima gradually declined, and its communities fell silent. The locals murmured to one another that it felt like the days before art first came to the island 30 years ago. It was as if the whole island, which usually enjoys a constant stream of tourists, had been transported back in time to a few decades ago.

Around 100 years ago, the small island of Naoshima began to grow prosperous thanks to a giant industrial project in copper smelting established by Mitsubishi. Even today, around 70 percent of the island’s population is employed in Mitsubishi-related workplaces. When the population nosedived as Mitsubishi pursued the mechanization and rationalization of its operations in the 1960s, Naoshima made its initial foray into tourism under the bold leadership of mayor at the time, Chikatsugu Miyake. The population continued to decline from a peak of 7,725 in 1959 and now stands at around 3,000, but annual tourist numbers have ballooned from 11,000 in 1990 to 730,000 in 2019. Nonetheless, the “small islands” of Setouchi that have witnessed stunning growth in their tourist numbers over the past decade continue to grapple with the problem of population decline.

A “landscape” created over many years by the natural environment and the people who live in it is discovered by visitors from the outside, becoming an attractive tourist asset. This landscape becomes further interconnected with content and imagery that people find captivating. This goes for the poetic epithets in the ancient Manyoshu anthology, the scenes depicted in historical scroll paintings, the scenes of movies and computer games, and even contemporary art. However, the images generated by outside observers are consumed and forgotten over the course of time. A landscape that has been formed over a long period can sometimes be altered dramatically by tourism; it may appear unchanged but be divested of content or bereft of substance. An example is the case of an ancient streetscape that becomes famous and is carefully preserved, but devoid of any signs of life other than tourist visitors. Surely there is a need to adopt a long-term perspective as we continue to reflect on and engage with such landscapes.

I am not an expert in tourism studies, nor do I yet have a detailed knowledge of Naoshima. This project is thus part of my process of investigating and familiarizing myself with Setouchi and Naoshima: it is a work in progress. In this project I do not seek to uncover and present historical truths, nor to create and exhibit my own works of art. In producing this exhibition in the fictitious space we call a museum, I hope to share with both locals and tourists viewing the exhibition the process of digging through the deposits accumulated over 100 years of tourism in this region, and thereby generate a space where we can imagine a little of what the future holds for Setouchi and Naoshima.

Finally, I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere thanks to Haruki Tanaka, who provided valuable scrapbooks of newspaper cuttings related to Naoshima beginning in the 1980s, and all others who provided materials and other forms of assistance.

Motoyuki Shitamichi (Chief Director of the Museum)

*1. Kanzaki, Noritake (2011) “Tabi to Kanko no Gaishi” [An unofficial history of travel and tourism], in Institute for the Culture of Travel, Tabi to Kanko no Nenpyo [Chronology of travel and tourism], Kawade Shobo Shinsha.

*2. Nishida, Masanori (1999) Setonaikai no Hakken [Discovery of the Seto Inland Sea], Chuokoron-S

[ 02 瀬戸内「百年観光」資料館 映画館 /Setouchi " Hundred Years' Tourism " Museum CINEMA ]

瀬戸内「百年観光」資料館の展示終了後、空間を映画館に改装。

瀬戸内を舞台にした映画を上映する、小さな島の小さな映画館を始めます。

After exhibition "Setouchi " Hundred Years' Tourism " Museum", we changed space from gallery to cinema.

This small cinema is screened movies set in Setouchi.

会場:瀬戸内「百年観光」資料館

9月7日(月)13:30~ 「二十四の瞳」 監督:木下惠介 主演:高峰秀子

9月12日(土)13:30~ 「喜びも悲しみも幾歳月」 監督:木下惠介 主演:高峰秀子

9月14日(月)13:30~ 「釣りバカ日誌1」 監督:栗山富夫 主演:西田敏行

9月19日(土)13:30~ 「男はつらいよ 寅次郎の縁談」 監督:山田洋次 主演:渥美清

対象:直島在住もしくは勤務の方

料金:無料 ※ご予約が必要です。

※新型コロナウイルス感染症の拡大防止のため、受付での検温、マスクの着用、手指のアルコール消毒、さらに室内の換気と空間に最善を勤めています。

:::::::::::::::::

第1回 瀬戸内「 」資料館

[ 01 瀬戸内「緑川洋一」資料館 /01 Setouchi " Yoichi Midorikawa " Museum ]

宮浦ギャラリー六区(直島)

2019.9/28-11/24

瀬戸内の風景と向き合い続けた写真家緑川洋一を調査し展示します。

We research and make exhibition photographer Yoichi Midorikawa who kept being confronted with the landscape of Setouchi by camera.

企画監修:下道基行

デザイン協力:橋詰宗

内装協力:能作文徳

宮浦ギャラリー六区

瀬戸内「緑川洋一」資料館

プロジェクト名:瀬戸内「 」資料館(監修:下道基行) 写真:宮脇慎太郎

協力:公益財団法人 福武財団

・・・・・・・・・・・・・

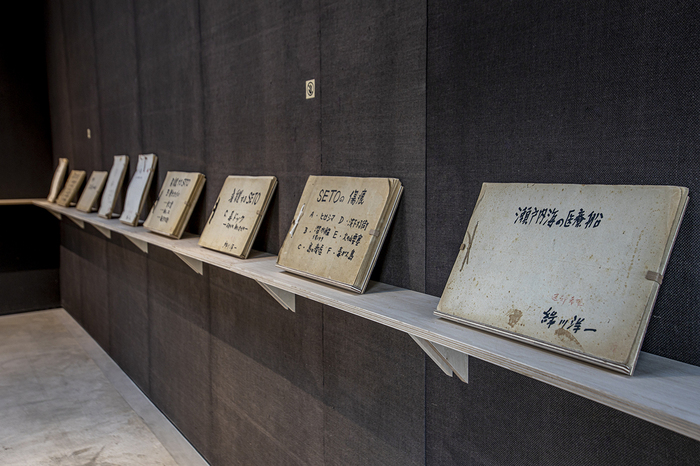

01. 瀬戸内「緑川洋一」資料館

《瀬戸内「 」資料館》の第1回のテーマは、岡山県出身の写真家、緑川洋一(1915-2001)です。彼の活動を調査した展覧会を開催します。

企画のきっかけとなったのは、ベネッセホールディングスが収蔵する《白い村》(1954)という白黒写真シリーズとの出合いでした。これらは終戦後の瀬戸内の産業や人々を独自の視点で撮影したものです。

緑川は日本を代表する写真家の一人で、平日は岡山駅前の「緑川歯科医院」で歯科医を生業としながら、日曜日にはカメラなど撮影機材の入ったリュックを背負い、瀬戸内や各地を撮影し続け、生涯「アマチュア」を貫いた写真家です。

緑川は戦前から写真雑誌に投稿を始めました。写真家であり編集者でもあった石津良介の紹介により、植田正治や秋山庄太郎、林忠彦などと写真家集団「銀龍社(ぎんりゅうしゃ)」(1947年設立)に参加するなど、戦前戦後の日本の写真家たちと影響を与えあい、活動を続けました。1960年以降、瀬戸内海の輝く水面と船や灯台のシルエットなどをカラー写真で捉えるようになります。そして、カラー写真の表現に独自の絵画的手法を織り込む方法を確立し、写真家として確固たる地位を築きました。2001年に亡くなるまで、生涯にわたり日本全国の風景や地元瀬戸内と向き合い続け、数多くの作品を残しました。

シリーズ《白い村》はドキュメンタリーの手法で撮影されていますが、緑川独自の絵画的手法の片鱗も見え隠れする、キャリアの過渡期のシリーズといえるでしょう。それは、ちょうど同時代の作家として緑川に影響を与えたとされる土門拳と植田正治の手法が独特のバランスで溶け合ったようにみえます。緑川は1960年以降、独自の表現手法を模索し、戦後をたくましく生きる人々の様子を風景とともに記録するシリーズをいくつも作っています。ただ、その多くは初期代表作の写真集「瀬戸内海」(1962/美術出版社)に断片的に収められていますが、シリーズ作品や写真集としてまとめられた形で日の目を見ることはありませんでした。近年では、2005年に岡山県立美術館で「緑川洋一とゆかりの写真家たち 1938-59」(企画:廣瀬就久)と題して、カラー写真ではなく、1960年代以前の白黒写真のシリーズを丹念に取り上げた企画展が行われるなど、戦前戦後の緑川の創作活動に注目が集まっています。

今回は、シリーズ《白い村》、さらにかつて岡山県岡山市西大寺に存在した「緑川洋一写真美術館」(1992-2001)で常設展示されていた1950年代のカラー以前の絵画的手法を使った《夜の釣舟》(1954)、《月明の海》(1956)などを展示します。

それとともに、生涯80冊以上の写真集を制作した緑川の写真集や掲載誌を収集し、さらに1940年から50年代にかけて撮影された未完作も含むシリーズの構想が記録された自作のファイルを、ご家族が大切に保存されていた緑川のスタジオより発掘し、これに光を当てました。

現在の美術界では、写真を一点のオリジナルプリントとして絵画のように美術作品として扱う傾向にあります。しかし本来、多くの日本の写真家は写真同士の連続性に意識を向けた「組写真」や「シリーズ」の制作を重視し、それを提示する最良の手法として「写真集」の出版に特別な意味を与えてきました。それによって質の高い写真集が多数生みだされ、日本の写真集文化が醸成されてきました。今回、ご家族の協力を得て、戦後間もなく撮影・制作された写真や構想段階のシリーズの手書きファイルから、緑川がどのように風景と向き合い、シリーズ作品として形にしようとしたかを探っていきます。

終わりに、今回、まるで時が止まっているかのように保存された緑川さんの制作スタジオや作品倉庫を何度も「フィールドワーク」し、多くの貴重な資料や写真を見せていただきました。時々、ポートレイトの緑川さんと目があう瞬間があり、写真家としても活動する自分としては、自らの死後に何者かがスタジオを歩き回り、未発表のファイルを読まれることを想像し、少し複雑な思いと共に重い責任を感じています。写真や風景と向き合い続けてきた一人の「先輩」のシリーズをつくる思考や手さばきを、残された資料より学ばせていただきたいという思いが次第に強くなっています。今回は、残された多くの資料すべてに目を通せた訳ではありません。もしこの資料館が今後も何年か続けることができるなら、この先もフィールドワークを継続し準備を重ね、再び新たな《瀬戸内「緑川洋一」資料館》を開館できたら幸甚です。

最後に、大きなお力添えをいただいた緑川さんのご家族のみなさまに、この場を借りて御礼申し上げます。

下道基行(資料館館長)

01. Setouchi “Yoichi Midorikawa” Museum

The first theme of the Setouchi “ “ Museum project is Yoichi Midorikawa (1915-2001), the photographer born in Okayama Prefecture. We are holding an exhibition which investigates his work.

The impetus for this project was an encounter with the black and white photo series called “Shiroi-mura” (White Village, 1954) in the collection of Benesse Holdings. In this series, he photographed the post-war industries and people of Setouchi from a unique perspective.

One of Japan’s foremost photographers, Midorikawa remained a life-long “amateur” photographer, making his living as a dentist on weekdays at the Midorikawa Dental Clinic in front of Okayama Station, while on Sundays, he shouldered a backpack loaded with his camera and photography equipment to photograph Setouchi and many other places.

Midorikawa began contributing to photography magazines prior to WWII. He remained active, joining the photography group called Ginryusha (founded in 1947), which included members such as Shoji Ueda, Shotaro Akiyama, and Tadahiko Hayashi via an introduction by photographer and editor Ryosuke Ishizu, and influenced Japanese photographers in the pre-war and post-war eras. In 1960, he began capturing the shimmering waters of the Seto Inland Sea and the silhouettes of lighthouses and ships, etc., in color photographs. He established a style that incorporated unique painterly methods into his color photo depictions, consolidating his status as a photographer. Until his passing in 2001, he continued to engage with landscapes across Japan and his home of Setouchi throughout his life, leaving behind a large body of work.

While the “Shiroi-mura” series was shot using documentary techniques, it can be described as a turning point in his career, offering glimpses of Midorikawa’s unique painterly methods. It appears to be a distinctively balanced blend of the techniques of Ken Domon and Shoji Ueda, contemporary artists believed to have influenced Midorikawa. From 1960 onward, Midorikawa explored his own unique modes of expression, creating numerous series recording people living life vibrantly in the post-war era and the landscapes surrounding them. While many of them are collected fragmentarily in “Setonaikai” (Seto Inland Sea, Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 1962), a collection of his early representative works, they have not seen the light of day in the form of complete series and photo collections. In recent years, attention has focused on Midorikawa’s creative activities in the pre-war and post-war eras, including an exhibition in 2005 at the Okayama Prefectural Museum of Art titled “Midorikawa Yoichi and His Circle, the Early Years: 1938-59” (Planner: Naruhisa Hirose) which meticulously covered not his color photos, but rather the black and white series he created prior to the 1960s.

In addition to the “Shiroi-mura” series, we also exhibit works such as “Yoru no tsuribune” (Fishing Boats on the Night Sea, 1954) and “Getsumei no umi” (Moonlit Sea, 1956). They were once permanent exhibits at the now-defunct Yoichi Midorikawa Museum of Art (1992-2001) in Saidaiji, Okayama in Okayama Prefecture, in which he used the painterly techniques that predate his color photos of the 1950s.

It also gathers Midorikawa’s photo collections, of which he produced more than 80 during his lifetime, and magazines he was published in, and sheds light on the personal files discovered in Midorikawa’s studio, carefully preserved by his family, which record his ideas for series shot during the period from 1940 through the 1950s, including uncompleted works.

In today’s art world, there is a tendency to treat the single original print of a photo as a work of art in and of itself, much like a painting. However, many Japanese photographers normally emphasize creating photo sequences or series which consider the relationship between photos, and this has imparted a special meaning to publishing photo collections as the optimal means of presentation. This has given rise to many photo collections of excellent quality, and helped to foster the culture surrounding photo collections in Japan. With the cooperation of his family, we will explore how Midorikawa engaged with landscapes and approached capturing them in a series of works from the photos shot and produced shortly after WWII and handwritten files on his series in the conceptual stages.

Finally, I did fieldwork for this project on many occasions at Midorikawa’s production studio, which is preserved as though frozen in time, and the repository of his works, and I was allowed to see many precious documents and photos. Sometimes, I meet the gaze of Midorikawa’s portrait for a moment, and as an active photographer myself, I imagine someone walking around my studio after my death, reading my unreleased files, and I feel a rather complex mix of emotions coupled with a heavy sense of responsibility. In engaging with photography and landscapes, he is a senior colleague to me, and my desire to study his surviving documents so that I might understand the thinking and handiwork behind his series has continued to grow. That is not to say that I was able to look through all of the many surviving documents during this project. If I can keep this museum open for the next few years, I hope to be able to continue my fieldwork, prepare it carefully, and open a new Setouchi “Yoichi Midorikawa” Museum.

In closing, I would like to take this opportunity to thank Midorikawa's family for their incredible support.

Motoyuki Shitamichi (Chief Director of the Museum)

・・・・・・・・・・・・・